Nothing says Thanksgiving like acknowledging the pillaging that came along with it.

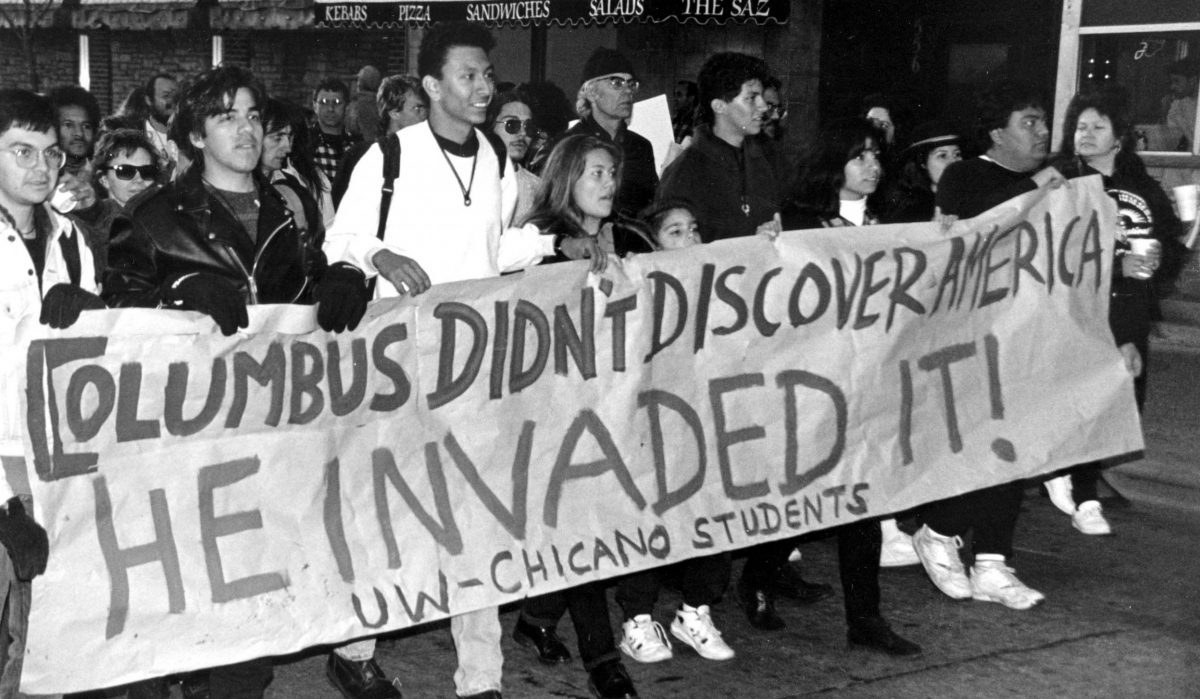

While reflecting on what you are thankful for with your friends and family, take some time to reflect on the numerous attempts that the U.S. has made to eradicate Native people. How ironic is it that a holiday centered around tradition and family was created while trying to rid Native people of those same things? Native heritage has been under attack through displacing children from their families by way of adoption, forcibly assimilating children in boarding schools, trying to overturn ICWA (Indian Child Welfare Act) and more tactics like blatant violence and blood quantum laws. Has hatred always been so intricate?

It started with Richard Henry Pratt. He was an officer during the Civil War that started an “experiment” while ordered to hold Native prisoners of war. This experiment was one of assimilation, and the results that Native people could indeed be civilized was given to the U.S. government. In 1879, the government decided to fund Pratt’s assimilation project, the Carlise Indian Industrial School. This became the first off-reservation boarding school for Native American children. A boarding school would seem harmless if the founder’s motto wasn’t “Kill the Indian, Save the man.”

Children were forcibly taken and put into this school miles away from their homes where their hair was cut, names and style of dress changed along with their language and religion. If the parents did not give their children up, they were met with consequences like lowered food rations and even imprisonment. The tactic of indoctrinating children was effective since they were young and vulnerable. The children grew up not being able to communicate with their families. Pratt started circulating “before and after” pictures of the students as propaganda that lead to the opening of nearly 300 similar schools across the U.S. In disconnecting these children from their families, and introducing Eurocentric standards of living, they grew up to be essentially disconnected from the land, the main vehicle for expanding the United States. In less than twenty years, two-thirds of native land was taken.

As time went on, indigenous activism grew alongside the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. Along with the activism, reports of abusive conditions at these assimilation boarding schools were grounds to have them closed. Unfortunately, when there is a will, there is a way. As the boarding schools started to decline, the next attempt to “civilize” natives was through adoption. The process of adoption was much cheaper than running a school and targeted a group even younger than the boarding schools did. This federal program, lasting from 1958-1967, titled the Indian Adoption Project (IAP), was a platform for native children to be adopted into white families. Similar to the assimilation schools, the narrative of the “savage” needing the white savior was spread. Native children were marketed to white families as “forgotten” or “orphans in need” when that was not the case.

The children being adopted were not orphans, just regular children being taken from their homes. Social workers would classify circumstances like too many family members in the house, lack of modern plumbing, and poverty as grounds to have children removed. The IAP was documented as a success. On paper, the children were adapting well when in actuality, they were driven to drug abuse, suicide attempts, and mental health issues. In 1977, the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) was passed, prioritizing extended family members, other native families, or tribes when adopting native children. As family and lineage are large parts of native culture, ICWA is important in conserving indigenous tradition. Yet, to this day, ICWA is constantly being attacked. White families that have adopted native children find the act to be discriminatory by race. Hmm, sort of like the whole IAP itself?

Opposite the one-drop rule in African American history, where one drop of “black blood” automatically makes the person black, one drop of anything that is not native blood makes a person less native. Being pure blood native is held in high esteem, so for anyone that is not, it allows room for division in their community. Blood quantum laws are sets of laws enforced by the federal government to limit citizenship into different tribes. Blood quantum is the amount of native blood one has and that determines Native American identity. However, different tribes require different percentages in order to gain tribal citizenship.

The U.S. government issues Certificates of Degree of Indian Blood, documenting blood quantum that was calculated using the original members of various tribes counted in early census rolls. Yet, the officials that established the blood quantum for the original tribe members did not know the native ways to establish them. It was often based on appearance. As complex as blood quantum seems, the goal is clear – land. Native culture and tradition are heavily tied to land and tribes. As time goes on, native blood will “dilute”. Leaving fewer tribes around to claim their land. When has America ever said “no” to available land and resources?

There are no conspiracy theories, being contrarian or unnecessarily radical. Like most racial injustices, there were actual U.S. money and policies in place trying to eradicate native people and their traditions in order to serve the American interests of land and power. As the leaders of the free world, many countries have followed the American mistakes of the past. We are different in being the only ones that have not apologized or even acknowledged this country’s racial wrongdoings. This Thanksgiving there is nothing wrong with being thankful and stuffing your face to oblivion, but let’s not celebrate the founding of one nation by destroying another. For more information, check out this piece on blood quantum, and watch these videos on adoption and race.