In the wake of the 2019 Met Gala, themed around Susan Sontag’s 1964 essay, ‘Notes on Camp’, I thought it would be fun to look into the origins of one of the campiest trends which never truly goes out of style– animal print. In my timeline, I’ve considered the shifting historical significance of animal prints and furs and included icons of the sartorial staple- from ancient kings and queens to rockstars and supermodels- always baring in mind Sontag’s 24th note, which states that ‘when something is just bad (rather than Camp), it’s often because it is too mediocre in its ambition. The artist hasn’t attempted to do anything really outlandish. (“It’s too much,” “It’s too fantastic,” “It’s not to be believed,” are standard phrases of Camp enthusiasm.) These looks fully embrace that accusation of being ‘too much’- revealing in the power, status, flamboyance, and ostentation connoted with animal print.

Prehistory & Pop-Culture

Bamm-Bamm Rubble as portrayed in ‘The Flintstones‘

My idea for this article was actually sparked by the most unlikely of style icons- Bamm-Bamm Rubble, from The Flinstones. Initially, I wanted to compile a simple rundown of iconic animal print looks from pop culture, and the stone-age toddler -who made his first TV appearance 1963 in the show’s 4th season- seemed a great start to my list. The prehistoric premise of this cartoon made me consider just how far back humanity’s love for animal print and furs might be traced to, spurring me to look further into the history of the trend.

Animal skins were first worn out of necessity- Neanderthals used the hides of the animals they hunted to keep themselves dry and warm. There is, of course, a mystery surrounding the possibility that these first clothes had other primary purposes, perhaps as tools of ‘magic, cult or prestige’. One of the oldest examples of clothing ever found -those of Ötzi, the ‘Iceman’, a well-preserved mummy of a man who lived over 5000 years ago found in 1991 in the Ötztal Alps- were largely comprised of animal skins. Although not quite as visually distinctive as Bamm-Bamm’s outfit, Ötzi’s clothing was made from an array of furs and hides; his belt, leggings, loincloth, and shoes were all made of leather, and he also donned a bearskin cap and a coat comprised of a patchwork of different colored furs.

Ancient Egyptian Royalty

Nefertiabet, an ancient Egyptian princess wearing a leopard gown / King Aye, the sem priest performing the “Opening of the Mouth” ritual on the mummy of Tutankhamun

Unlike Ötzi’s native Europe, both leopards and cheetahs were common in ancient Egypt, where cats were closely associated with ideas of divine energy and were thus tied to ideas of power and the gods themselves. Most famously Bastet (or Bast), the goddess of the sun worshipped throughout most of ancient Egyptian history was first portrayed as a lioness, with her depiction gradually morphing into an anthropomorphized domestic cat figure. In addition to her solar connections, Bastet was later honored as the goddess of fertility, pregnancy, and childbirth, and at times portrayed alongside a litter of kittens. These beliefs influenced her worshipper’s sartorial customs; in the Middle Kingdom, leopard heads and skins – and sometimes those of cheetahs- were believed ‘to guarantee rejuvenation and fertility’; there was thus a custom of including images of leopard heads in girdles worn by women wishing to conceive.

Another divine figure, Seshat, the goddess of wisdom, was linked to feline power through her dress- and is often pictured wearing a leopard or cheetah hide. Indeed, the attitudes to the wearing of such skins changed vastly over the numerous Egyptian dynasties. In her ‘Survey of Historical Costume’, Phyllis G Tortora writes that ‘in very early representations, one may see the skin of a leopard or lion fastened across the shoulders of men. In later periods…wearing animal skins was reserved for the most powerful elements in society: kings and priests’. Here, unlike in prehistoric times, there is the certainty that animal skins were donned for their powerful connotations- as a status symbol rather than out of sheer necessity.

Most interestingly, I found out from Tortora’s book that later on, furs themselves were no longer worn, but were replaced out of respect by ritual garments which simulated the animal skins- leopard spots were painted onto a cloth. These very first instances, of what we might deem fake fur, were created in reaction to the growing Egyptian belief in magic- men no longer saw themselves as worthy of wearing ‘the skin of a fierce beast’, as ‘the powers of the animal [might] magically transfer to the wearer’.

Historical Portraiture

Madame Bergeret de Frouville as Diana (1756) by Jean Marc Nattier / Coronation portrait of George III (1762) by Allan Ramsay

In the 18th century, animal skins were utilized in Western portraits of nobility as both a way of concealing and flaunting one’s status. The above 1756 painting of Madame Bergeret is what’s known as a ‘disguised portrait’- in fact, it’s only recently been possible to identify her, ‘owing to the appearance of a copy with the arms of both the sitter and her husband’. As if wishing to avoid recognition, we see Nattier’s sitter in the guise of Diana, Roman goddess of the hunt, from classical mythology; not only is her bow and quiver of arrows a blatant symbol of this figure, but the pelt of leopard fur tied around her shoulders appears to be a trophy from a successful hunt. In this case, animal print is used as a means of both concealment and a tool to indulge in fantasy- a way for the aristocracy to play dress-up.

Furs were also at this time used as an explicit display of status and ostentation in royal portraits. From medieval times, the linings of coronation cloaks and other such garments worn by high-ranking peers and royalty were made from the furs of ermines– white stoats with black-tipped tails. Many of these animals were needed to produce just one luxurious ermine lining like the one worn in the above portrait of George III (and by countless other monarchs before and since), with that distinctive pattern of black diamonds on white made from their hanging tails. Rarity and expensiveness was key to the royal fixation on ermine fur, which interestingly became linked with Western European courts through a symbolic legend, which stated that an ermine would “rather die than be defiled”, as translated from the Latin, “potius mori quam foedari”- the fur itself was thus a representation of royal ‘moral purity’.

60’s Sex Kitten – Eartha Kitt

Eartha Kitt alongside a cheetah, photographed by Michael Ochs circa 1970 / Eartha Kitt pictured performing on her television series ‘The Eartha Kitt Show’ in 1965

Making a big leap forward now in the history of animal print, Eartha Kitt was another name which instantly came to mind as an icon of the trend, from photos I’ve seen of her the 1960’s. In fact, the demand for leopard print had been increasing for decades before it was adopted by the songstress- since the end of World War Two, as women’s ‘desire for opulence and extravagance became the center of fashion’, following the necessary but dull practicality of wartime clothing. Christian Dior was one of the most famous to adopt the print into his designs – declaring ‘if you are fair and sweet, don’t wear it’ – a suggestion of danger and sexiness which set the tone connoted with the pattern for years to come.

Throughout the 1940s and ’50s, Kitt’s performance looks were fairly demure, matching the other singers of the era in feminine silhouettes and pearls – as Rachel Lubitz points out in her article on the icon, ‘she was one of only a few successful black women in music at the time, so how could she break the rules? Even in the studio, she promoted the typical ladylike glamour’. In the 60’s though, as ‘ladylike’ fashion was eclipsed by the newer, tighter, and shorter silhouettes and Eartha’s career went from strength to strength, she grew bolder- both in terms of her political outspokenness and activism, and her style- becoming one of the first women of color in the US entertainment business to totally embrace and take risks in her fashion choices.

Rather than ‘an hourglass of silk or satin’, she donned skin-tight cheetah-print dresses and pencil skirts, cropped two-pieces like the one above and perhaps most famously feline, played the perfect Catwoman in the campy 60s TV serialization of Batman (with producer Charles FitzSimons commenting that She was a cat woman before we ever cast her as Catwoman. She had a cat-like style). The era marked the expansion of Kitt’s public persona, from an already recognized singer and dancer to a bonafide sex-symbol, who doubtlessly inspired women in the industry after her- such as Tina Turner– to take to the stage in entirely animal print ensembles.

Glam Rock God – Marc Bolan

Marc Bolan in 1977, photographed by Chris Walter / Bolan in 1973, photographed by Jan Persson

Best known as the lead singer of British rock band T. Rex, Marc Bolan was one of the pioneers of the glam rock movement in the 1970s. The genre was self-glorifying, decadent and even superficial, a conscious rejection of the revolutionary rhetoric saturating rock music at the end of the 1960s. In the style of their music -which looked to the simple structures of bubble-gum pop for inspiration- and the style of their clothes, glam-rockstars existed on the periphery of over-intellectualized, macho rock culture; they were, in the words of critic Robert Palmer, “rebelling against the rebellion.”

Animal print, which Bolan wore in abundance- from leopard print jumpsuits and accented jackets to zebra print muscle-tees, mirrored this embrace of both trashiness and femininity. Combined with his penchant for top hats, platform boots, feather boas, and glitter, all of which he wore onstage, he was the epitome of campy flamboyance. Whilst the origin of his playfulness with makeup is unclear -with some saying it was the idea of his personal assistant, Chelita Secunda, whilst Bolan himself stating in a 1974 interview that he noticed the glitter on his wife’s dressing table prior to a photo session and casually daubed some on his face there and then- it’s obvious that Marc had a devil-may-care attitude to gendered expectations of style, and was at the forefront of embracing an androgynous aesthetic as a male musician.

Bolan’s style was wild and electrifying- ‘part dandy, part working-class wide-boy’, his mass of hair and skin-tight suits transfixed viewers of the BBC’s Top Of The Pops in T. Rex’s first appearance in 1971, before the band’s string of hits made them superstars. Other performers and fans began to don variations of his style- and the era of glam and glitter rock was born: Bolan was, according to music critic Ken Barnes, “the man who started it all”.

King / Queen of Camp – Divine

Cover art for ‘Shake it Up’ (1983) / Divine as Dawn Davenport on the set of John Waters’ Female Trouble (1974)

Possibly the main reason why I so closely associate animal print with camp is the glorious Divine. Arguably the most iconic drag performer (or as he preferred, character actor) of all time, Harris Glenn Milstead – stage name Divine- was an actor, singer, and performer most famous for his legendary roles in the films of John Waters, the director dubbed ‘The Pope of Trash’ by William Burroughs. The pair met when Divine was 16 in his native Baltimore, with Waters having recently been expelled from NYU; bullied for his weight and his effeminacy, he found both a friend and an artistic collaborator in John which would last a lifetime. By the age of 18 Divine began hairdressing, and simultaneously developed an interest in drag and in showmanship, throwing lavish parties and charging the expenses to his fathers’ credit card.

Enamored by his female persona, Waters gave Divine his name, claiming that he was “the most beautiful woman in the world, almost,” a partner in crime ‘with whom he wanted to make wildly, delightfully trashy films’. Their cinematic efforts grew wilder after their first films in the 60’s- with 1972 seeing the release of the notorious ‘Pink Flamingos’, which became a cult favorite at midnight-movie screenings, launching Divine’s career as an underground star. The film is fantastic- weird, campy and vulgar- and is perhaps most notable for its final scene, in which Divine eats fresh dog feces- for real. And what does Divine wear in the preceding scene? Nothing but a leopard print bra and a skin-tight skirt.

Divine often wore all-over animal print- a sign that he followed Water’s suggestion to ramp up his already extreme aesthetic. Divine would become the ‘Godzilla of Drag’- donning miniskirts and bodycon dresses in the bold fabric which drew attention to his larger than life frame, with ever more ostentatious makeup and hair. Rejecting traditional glamour and femininity was something drag queens at the time didn’t do, but it worked for him. He built a cult following from his acting, club appearances and songs such as ‘Shake it Up’ -which he performed on The Tube, in a fluorescent leopard print mini-dress, and donned tiger print for the cover of, his wild white-blonde hair in the above picture showing how obviously inspired the designers of Disney’s Ursula were by his look.

His legacy is one of rejecting normal notions of taste- in the words of Waters, “he made all drag queens cool. They were square then, they wanted to be Miss America and be their mothers… He broke every rule. And now every drag queen, everyone that’s successful today is cutting edge.”

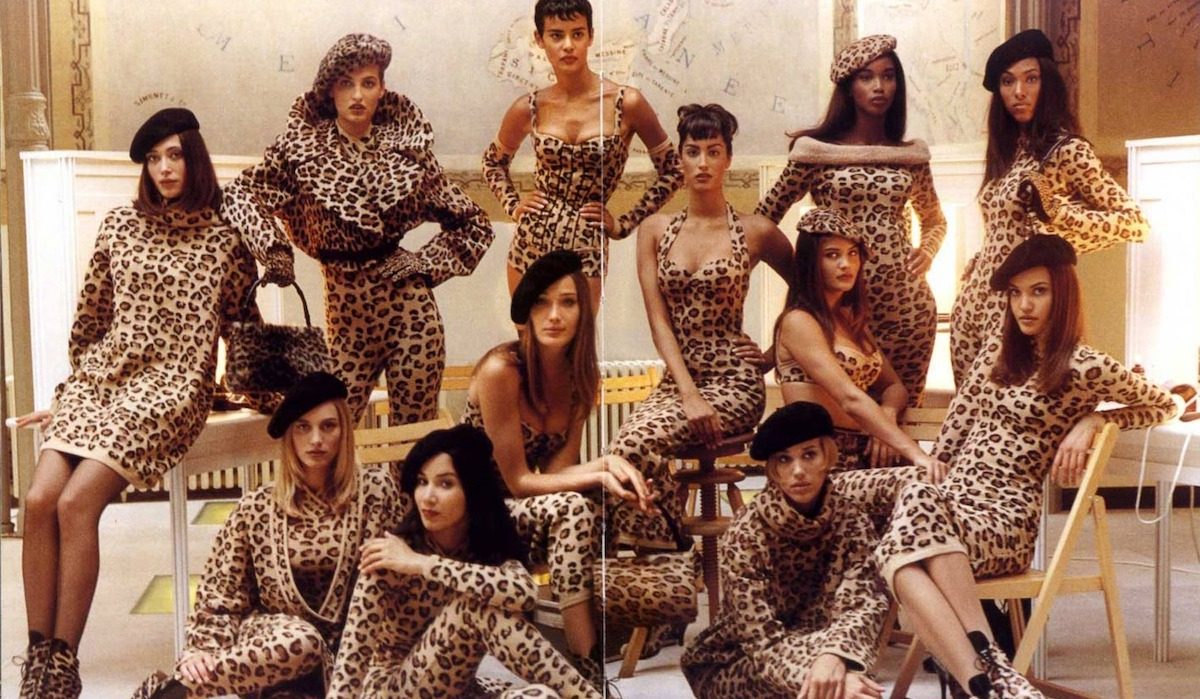

Azzedine Alaïa & Naomi Campbell

‘Wild Things’, Harper’s Bazaar by Jean Paul Goude (2009)/ Naomi Campbell in Azzedine Alaïa Ensemble from the Leopard Collection, Vogue Italia (1991)

The 90’s saw the connotations surrounding leopard print shift from the overt (and glorious) trashiness of the previous two decades, into the impossibly chic. The man behind this change was none other than Azzedine Alaïa, whose daring Fall/Winter 1991 collection -pictured in the cover image of this article- saw the supermodels of the day clad in head to toe leopard print. The print was emblazoned on leggings, skirts, coats, bustiers, gloves, berets, bags and the body-con knit dresses for which he was known now elevated by a new and almost feral sense of ‘animal magnetism’. In this collection more was definitely more in terms of the print, and yet the simple silhouettes of his designs made the subversive pieces appear effortless and easy, and doubtlessly the 90’s leopard print moment, revived most recently by Kim Kardashian West, who rocked an archival Alaïa piece first sported on the runway by Deon Bray.

It was, however, Naomi Campbell who was -and arguably continues to be- the real face of the trend. Not only did she walk in the show, but she was photographed in countless editorials in both the Alaïa collection and various other animal print get-ups. Some of her most iconic shoots- such as the Vogue Italia spread shot by Michael Roberts, or the Cosmopolitan Australia swimwear article in 1993 saw Naomi clad entirely in leopard. And it’s a look which has stayed associated with the OG supermodel throughout her career; one of my favorite ever photos of her is the above shot from 2009, of her running alongside a cheetah in a cheetah-print cocktail dress, and a wave of nostalgia went over me when I saw this spread from a 2010 issue of Vogue Russia, which sees her wearing some of those original Alaïa pieces. Naomi’s penchant for animal print might have morphed into something a little more grown up– just as Alaïa’s collection saw the trend morph into the mainstream- yet her confidence in the prints shows that she remains as bold as ever.

Mel B – Scary Spice

Mel B performing at the Brit Awards ceremony in 1997, photographed by Fiona Hanson/ Mel B pictured in a vintage Spice Girls poster (source unknown)

When it comes to the Spice Girls (who are coincidentally currently on their reunion tour of the UK), it’s always been Mel B whose wardrobe has had a special place in my heart. Her nickname, ‘Scary Spice’- the potentially problematic nature of which she herself has dispelled in interviews, penning the moniker to her brash attitude; “I’m very kind of in-your-face. I was even more so back then. I was, what, 17, 18, like, ‘What! What do you want?!’ So I guess I could have come off as Scary. But I like my name.”

And her wardrobe was arguably the most in-your-face of any of the girls- she seemed to own a seemingly endless supply of animal print outfits- in fact, she’s probably rocked the style more times and in more ways than any other individual on this list! Even when the whole group donned pinstripe suits for the 1997 ‘Spice World’ premiere, you can see her little leopard bra peeking out. Fellow Spice Girl Mel C has stated in interviews that these distinct styles chosen by the girls themselves, “in those early days, it was the fashion in girl bands for everybody to dress the same, or kind of coordinate. But it just didn’t work for us,” she explained. “Picture Beckham in a tracksuit; she’d look ridiculous. And then me, in a little Gucci dress? It just wasn’t working. So, that’s when we decided to just be ourselves: We just started to wear what we’d been wearing to rehearsals every day, and then it evolved and became a bit of a caricature. But it was quite an organic beginning.”

So yes, the look became exaggerated- but Mel B’s wardrobe of not only iconic leopard print, but tiger (which she sometimes wore together), and snakeskin is fundamentally her. Completely rejecting the dull advice of countless fashion magazines- ‘less is more!’ they write, unconvincingly- Mel B’s so great because she loved to go totally over the top. And yet there are so many pieces from her 90’s and 2000’s wardrobe I wish I could steal, such the tiger print suit pictured above – particularly the trousers, which look unbelievably current paired with a black tank top– or this tie-front top I’m sure I’ve seen ripped off by a zillion Insta clothing brands. Not only do her 90’s looks make her a style icon today (and forever), but she clearly continues to hold animal-print close to her heart.

Tyler the Creator

Tyler on the red carpet of the Grammy Awards, 2018 / Tyler for Fantastic Man, photographed by Mark Peckmezian

As if the powder-blue suit, monogrammed Louis scarf, and fluffy white ushanka weren’t enough to make it so, Tyler’s reveal of his cheetah-spotted buzzcut on the red carpet of the 2018 Grammys tipped his outfit into being one of my favorite looks from one of the best-dressed men I can think of. I hugely appreciate the hairstyle not only for its aesthetic value (have I mentioned that I love animal print?), but I also as an example of the exciting ways that men can experiment with grooming without turning to makeup.

I knew the look reminded me of someone else- and sure enough a quick google search jogged my memory- that I’d seen this look rocked by another uber-successful young black man who was unafraid to be as flamboyant as any runway model, on one of the largest and most hyper-masculine stages in the world- the NBA. Whilst I love Tyler, and his version of the look is doubtlessly the most relevant to our generation, there’s no doubt that he was deeply inspired by Dennis Rodman’s leopard look, which was dyed and designed by JoJo Baby, one of Chicago’s original club kids and an all-around drag legend. The Chicago Bulls player and fashion hero who was famous for his ever-changing hair, sported the leopard look both on the court and off it; it even made an appearance in a 1998 Jay Leno interview.

Interestingly, back in March, my Instagram feed was flooded with pictures of João Knorr, both backstage and on the runway at the Versace menswear show in Milan with his blonde hair dyed in an uncanny resemblance to the rapper and sports star. Allure called it the ‘high-fashion debut’ of leopard-print hair, and went on to sing the praises of Guido and Davide, the ostensible brains behind the look- no credit was given to either Rodman or Tyler as inspiration, let alone to JoJo Baby.

This instance raises important and very modern questions of acknowledgment- why is a look worn by a white model, and sent down a catwalk by a white designer, praised as though it were never-before-seen? The trend for animal-print hair, designed by a queer POC – JoJo is a mixed-race son of a Greek immigrant father and a Native American mother- made famous by a black man, and worn most frequently by other African-American celebrities, like Nicki Minaj and Nick Cannon, is only valued in the mainstream when it’s appropriated by a powerful fashion house looking to profit off and exploit the trends created and popularised by POC.

In researching this article, I’ve realised just how significant the role of the queer community and POC have been in maintaining the modern use of animal print in clothing -keeping one of my favorite elements of fashion alive- with all of the 20th and 21st century figures on this list falling into one or both of those groups. I hope that in mapping the history of the trend in this way, I’ve been able to pay kudos to them, whilst showing NBGA readers how richly suggestive the use of animal print is- at once funny, campy and sexy, it is above all things a show of power and fearlessness- of being unafraid of being ‘too much’.